Report of the international conference to inaugurate the world federation of scientific workers

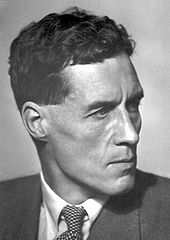

Professor P.M.S. Blackett

WFSW constituent Congress,1946

I want to take a few minutes in explaining a little  of the history of this gathering and the history of the Association of Scientific Workers. The British Association started at the end of the last war as a Trade Union, but ceased to be a Trade Union after a time and eventually became once again and affiliated with the Trades Union Congress in 1938. It started as a smallish body, mainly of academic Scientists, but in about 1936 started to recruit in the field of industrial Scientists and from that moment started to grow. It is now a body of some 16,000, including Associate Members who are not necessarily scientists but Laboratory Assistants and Technicians, which is very widely based in industry and also in the Universities of this Country. I mention these points so that all those who have not been in touch will be quite clear as to what sort of body the Association is. The driving force behind the growth of the body was two-fold: the pure Trade Union side, to make the career of the Scientist an improved career and attain standards in the usual way that professional Trade Unions work; and, on the other side to advance the use of science in the interests of the welfare of mankind, taking a broad view of what is science. Here we come to perhaps the greatest important contrast we must remember in our discussions namely the different status of scientists in various Countries whose histories are all different from our own. Here I think we must emphasise the difference between a body like the Association and the ordinary professional scientific organisation of each Country. Every Country has its Organisations. Usually they have something corresponding to an Academy or a Royal Society which generally embraces a certain section of the distinguished Scientists in the Country on all subjects. Some are small and therefore of a very high average age and others are larger and therefore on the average younger. The French and Russian academies are rather small and therefore have a rather high relative age of membership.

of the history of this gathering and the history of the Association of Scientific Workers. The British Association started at the end of the last war as a Trade Union, but ceased to be a Trade Union after a time and eventually became once again and affiliated with the Trades Union Congress in 1938. It started as a smallish body, mainly of academic Scientists, but in about 1936 started to recruit in the field of industrial Scientists and from that moment started to grow. It is now a body of some 16,000, including Associate Members who are not necessarily scientists but Laboratory Assistants and Technicians, which is very widely based in industry and also in the Universities of this Country. I mention these points so that all those who have not been in touch will be quite clear as to what sort of body the Association is. The driving force behind the growth of the body was two-fold: the pure Trade Union side, to make the career of the Scientist an improved career and attain standards in the usual way that professional Trade Unions work; and, on the other side to advance the use of science in the interests of the welfare of mankind, taking a broad view of what is science. Here we come to perhaps the greatest important contrast we must remember in our discussions namely the different status of scientists in various Countries whose histories are all different from our own. Here I think we must emphasise the difference between a body like the Association and the ordinary professional scientific organisation of each Country. Every Country has its Organisations. Usually they have something corresponding to an Academy or a Royal Society which generally embraces a certain section of the distinguished Scientists in the Country on all subjects. Some are small and therefore of a very high average age and others are larger and therefore on the average younger. The French and Russian academies are rather small and therefore have a rather high relative age of membership.

In the 17th century, our own Royal Society was very closely concerned with the relations of science to society, but became more isolated as time went on. In general, the Academies or Royal Society have their limitations in that they do not have any contact whatever with the rank and file Scientists in the Country as a whole, particularly in industry. They have very few members except for the few odd geniuses who are young, even in the academic field, and they are excluded from expressing an opinion which might be faintly, controversial on political matters.

Then there are professional Societies, the Royal Institute of Chemists and other bodies like that, which are, in various degrees, bodies for maintaining professional status in particular field of science. I have never known Institutes have any Trade Union function. Professional scientific bodies however a great part to play in Science in their own Country.

The Association of Scientific Workers differs from these in not being restricted to one Science, and we include Social Scientists also, and cover all grades of workers in the Laboratory from the young to the old, and the semi-skilled to the very high-skilled, and we are relatively free to take sides and express views of matters of practical importance, even though they have a political tinge. I think we were the first body of Scientists in this Country to come out with definite views about the application of science to society, – and a lot of other things. Actually, the world is changing and even the most neutral bodies, like the Royal Society, are increasingly concerned with these matters. The Royal Society has just begun a 3-weeks Conference which has been about 85% concerned with applied Science – Agriculture, Tropical Medicine, etc. That is an innovation for the Royal Society and I am very glad they have done it and that it has been a great success. Other bodies similarly are arriving at a greater realisation or the importance of applied science.

I have tried to give you some indication of how the Association of Scientific Workers has grown up and how it differs from other bodies. Each Country has its own problem and history and will therefore produce its own type of Organisation. What suits us does not suit other people, and that was originally one of the stumbling blocks in the way of forming an International Federation of Scientific Workers. There just did not exist in any other Countries the same background which could have produced bodies like the Association of Scientific Workers in that Country. Some were more or less alike, and some were very different. The particular stumbling block was that the A.Sc.W. is affiliated to the Trades Union Congress and that is not true of many other of the bodies. – But if you think of how we have grown up in relation to particular circumstances in this Country I think you will see and get in proportion and perspective the conditions under which each Country gave rise to each sort of Organisation. Dr. Wooster will tell you more himself of how when he was in Moscow last summer he had some discussion on forming a Federation, but it was considered impossible to form bodies which were at all like the A.Sc.W. – But at the Conference « Science and the Welfare of Mankind » in February, a great many discussion took place and it was considered eventually that there was sufficient bases to go ahead, provided we did not expect all the bodies we hoped to federate to be alike, and this Conference has been called on our initiative to see whether that assumption in correct – whether there are bodies who are sufficiently, alike in their aims to federate usefully.

Now I think it is very difficult to be quite sure how diverse types of bodies can usefully federate. It is quite clear that if you make an organisation too wide and include too many different kinds of types and interest, then you tend to get no firm decisions made on anything and every proposal has some compromise, and you do not do very much: on the other hand, you can be too sectarian and so will not federate with someone not of your own views, and you get nothing done. I think it is one of our points to see that we set up an Organisation which does something and which aims to have a reasonable basis of unanimity on fundamental tasks, e.g. my own personal view is that any Organisation definitely precluded from taking any line on the application of science that might be faintly controversial would be a doubtful body, to come into this, because unless we can do that I do not think we shall do very much.

There are, or course, an enormous number of problems at the moment which want discussing on an international basis. The Atomic Energy question will remain with us for a very long time, and that raises this very intricate question of the desirability, or otherwise, of extending specific organisation for the study of Atomic Energy on a world-wide basis. I think it is a difficult question to decide and I think there are dangers in concentrating too much attention on one particular thing as there are so many other things to be done at the present time. I think that Atomic Energy should be one of the chief things that we must deal with and our formulation of international policy is extremely important. I can imagine that an extremely useful synthesis of national viewpoints could be achieved through an Organisation of this sort and so far as I can see through few other Organisations. For obvious reasons you will not get the official academies because they will follow their own governing lines and there is no other international body which can together and discuss these things.

Then there is the question of food, which is certainly a problem which will be before us for the next few years and on which a great deal of discussion could usefully be done, although that is being done by other bodies as well.

There is the general question about which we hope to hear from the delegates from other Countries – the general part Science can play in the reconstruction of Europe and the other devastated Countries in the world.

Bringing together all the people who really, in fact, make the Science of the Country possible is particularly useful in Countries which have the ravages of war to repair and who are starting a big industrial programme. You could not get the A.Sc.W. type of Organisation in an entirely non-industrial Country, because you do not have the Industrial Scientist. It is bringing together the pure and the Industrial Scientists which is characteristic.

There are very many questions also which will want discussing – ethics, how Scientists are going to behave in certain circumstances, and their attitude to certain types of work for which the consequences are dangerous to the world. This raises questions of personal conscience, of National responsibility and your legal position as a Scientist, and world-wide morality.

We are very glad to welcome so many delegates here today. I believe there are some 10 organisations represented here officially and about 6 sets of observers, who have come to watch what happens and report back. Altogether there are some 30 delegates and 15 observers.

I think that is all I need to say by way of introduction. You have got a great deal of business to do, and I very much hope that something concrete will come out of it. The difficulty of steering the course between wanting to make too big and grand an Organisation which does not work and too small a one which does not inspire is very great. I hope seriously that you will go away with a very clear idea of certain definite tasks to do so that something will really come out of this.